[Page – 01]

TCRC and its Aim

The aim of TCRC as a society is to work towards the collection and dissemination of knowledge in the area of Textiles and Clothing, while collaborating with other researchers in this field of study.

India has a legacy of producing the most exquisite textiles, each with its own geographical and cultural marker. The same can be said for clothing, aristocratic as well as from other sections of society. Realizing the need for a common platform for exchange of knowledge in lost textile traditions as well as contemporary practices, a group of like-minded and dedicated researchers including academics, curators, conservators of textiles, designers of clothing, came together to set up TCRC – Textiles and Clothing Research Centre, to be launched formally on the 1st of February 2017, at the National Museum in the presence of Dr. B R Mani, Director General (National Museum).

The society’s website www.tcrc.in will work as a repository of information for interested individuals. TCRC will be publishing bi-annual e-Journals for its members. TCRC will also announce its first call for papers on the 1st of February 2017 and is planning to host the first international conference in November 2017. All details of which will be available on the website

[Page – 02]

In this issue: Dyes used in textiles

Contents

- Traditional Indian Textiles – Dye and Nomenclature

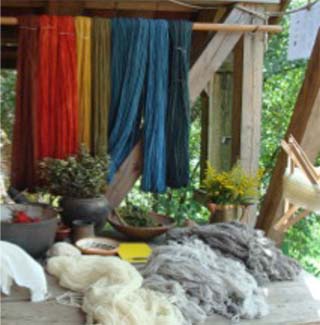

Author: Lotika Varadarajan in conversation with Anamika Pathak | Page: 03 – 04 – 05 - Tent Panel Illustrate Gandaberunda,

Author: Anamika Pathak | Page: 06 – 07 – 08 - Sustainable Approach to Rebuild Dyeing in Traditional Craft of Chamba Embroidery

Author: Rohini Arora | Page: 09 – 10 – 11 – 12 – 13 - Dyeing of Chanderi Silk with Natural Dyes

Author: Simmi Bhagat | Page: 14 – 15 – 16 – 17 - Dyeing Support Fabric in Textile Conservation: Dyeing Method of Silk Crepeline with Huntsman Lanaset Dye

Author: Smita Singh | Page: 18 – 19 – 20 - Natural Dyeing Workshop at CTR (Centre for Textile Research) Copenhagen, Denmark in August 2010.

Author: Toolika Gupta | Page: 21 – 22 – 23 - Visit to Rathgen-Forschungslabor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Author: Binoy Kumar Sahay | Page: 24 – 25 - Suggested Readings Related to Indian Textiles

Author: Zahid Ali Ansari | Page: 26 – 27 – 28 - Textiles and Clothing Related Upcoming Events | Page: 28

Chief Editor & Design: Smita Singh | Editor: Rohini Arora

Published & e-Owner: Textiles and Clothing Research Centre (TCRC)

Printed by: Textiles and Clothing Research Centre (TCRC)

Website: www.tcrc.in

Email: editorstcrc@gmail.com and infotcrcdelhi@gmail.com

Founder Members:

|

Lotika Varadarajan |

President |

|

Anamika Pathak |

Chairperson |

|

Toolika Gupta |

Secretary |

|

Binoy Kumar Sahay |

Joint Secretary |

|

Smita Singh |

Chief Editor |

|

Rohini Arora |

Editor |

|

Zahid Ali Ansari |

Treasurer |

|

Larah Rai |

Media Manager |

|

Archana Shastri |

Member |

|

Janaki Turaga |

Member |

|

Simmi Bhagat Member |

Member |

|

Md. Ali Nasir |

Member |

|

Sushmit Sharma |

Member |

Disclaimer: Statements and opinions expressed in the published papers are those of the individual contributors and not the statements and opinion of TCRC. All the respective authors are the sole owner and responsible of published research

(Regn. No. S/2056/Distt. South/2016)

(Under Societies Registration Act of XXI of 1860)

[Page – 03]

Traditional Indian Textiles – Dye and Nomenclature:

Lotika Varadarajan in conversation with Anamika Pathak

Dr. Pathak: The word ‘Kalamkari’ is from which language? Are there any regional names?

Dr. Varadarajan: The philosophy of nomenclature in India is very different from that followed by Islamic cultures and in the West. Items are identified not in terms of technique but their place of origin – be it food or textile items. The Dutch and French used terms like sits for painted, chits for printed (Dutch), les toiles peintes, les toiles imprimées, both subsumed in the term les indiennes (French), while the English preferred the term chintz which covered both painted and printed textiles. The term chit, speckled or dotted referred to the sprinkling of water on the cloth when left to dry in the sun to prevent fading. This gave rise to the word chintz. Chintz in India was made with the use of natural dye on cotton fabric through the processes of resist and mordant. Mordant could be applied either with a block made of terracotta, wood or brass or with a brush/pen like instrument, the kalam, and this was affected on a prewoven fabric. Resist would involve the placement of either treated mud or wax over the areas which were intended not to absorb the colour applied in the mordanted areas. The origin of the word kalamkari is derived from the two Persian words, qalam, pen and kari, craftsmanship, collectively meaning “drawing with a pen”. Persia also had a tradition of this craft but the appeal of the Indian

fabric lay in the excellence of the colour white which formed the background material and the vibrancy of the other shades. This term kalamkari was absorbed into Idian artisanal and trade vocabulary.

Dr. Pathak: Can one trace the origin of ikat dyeing? Where is ikat practiced in India?

Dr. Varadarajan: There are different theories as to the origin of the word ikat. Edward C. Yulo, Philippines is of the view that the technique of ikat was first developed by the Austronsian speaking seafaring group having their origin in Taiwan and the southern coast of China. From here they spread into insular Southeast Asia, Melanesia and ultimately into Polynesia. R.N.Mehta (Bandhas of Orissa, Journal of Indian Textile History, Vol, VI, 1961) mentions the double ikat woven by Bhulias in Orissa. Orissa had rich trading links with insular Southeast Asia and it is possible that the ikat traditions were absorbed through trade. It should however be remembered that except for the double ikat, gringseng, produced in the village of Tenganan, Bali, insular Southeast Asia has produced only single ikat. At this moment research is awaited on tracing the history of double ikat as well as the connection if any between the double ikat of Orissa, the Sambalpuri saris, and the double ikat found in the work of Patan salvis in Gujarat.

[Page – 04]

It is interesting to note the role of commerce and the linkages established through trade. Gujarat was the entrepot for the trade in black pepper of which Kerala was the sole producer. It was from Gujarat that its circulation in West Asia took place. It is possible that it was through this trade that Patan patola was introduced into Kerala. Not only is this much in evidence in the mural paintings of Mattancherry Palace, Cochin, but it also entered into the category of textiles given as a mark of honour by the monarch, the veeralipattu. There is no tradition of ikat weaving in Kerala and samples were brought in through trade.

Dr. Pathak: What is the earliest evidence of ikat in India? Is there any connection between ikat and plangi?

Dr. Varadarajan: As has already been stated the ikat tradition has been associated with the speakers of the Austronesian group. The Benaki Museum, Athens, has Yemeni ikat textiles of the tiraz category the earliest being dated to the 9th century. This technique could have been introduced to Yemen from Gujarat through trade contacts. The Central Asian tradition appears to have been derived from Yemen where it underwent further transformation. The twin processes of ikat and plangi are based essentially on the reserve technique. The processes found in western India include ikat, plangi and painted and printed textiles. In ikat the yarn is tie died prior to being woven. In plangi the fabric is first woven and then tie-dyed. The two techniques are quite different.

Dr. Pathak: What is the difference between the kalamkari practiced in South India and that in the Western region?

Dr. Varadarajan: Both are practised on cotton, which is cellulose fibre and thus resistant to dye. The constitution of this fibre is changed by the application of a mordant. The mordant can be introduced either by the block, which is generally true of Gujarat or it may be applied through the pen or qalam associated with South India. Mordant provides reasonable depth and permanence of colour. The major difference between the kalamkari of South India and Gujarat is that, in the case of the first the cotton fabric is fine, while in Gujarat it is generally done on thicker cloth. Usage of each was related to specific processes and techniques. Gujarat has a 12th century reference by Hemachandra to printing being carried out.

Dr. Pathak: Different techniques of pigment painting and their centres?

Dr. Varadarajan: Pigment painting is found in the khari painting of Gujarat and some of the pichhwais painted in Nathwada in Rajasthan and later in the Deccan.

Dr. Pathak: How much do we know about our past tradition?

Dr. Varadarajan: The find of a mordant dyed yarn in a cord to hold a necklace at Moherjodaro indicates the antiquity of mordant dyeing in South Asia. Ochre was one of the few colours, which cotton could absorb without mordant. As has been already stated to achieve the dyeing of cotton fabric in many hues, the fabric had to be initially treated with a mordant, which set up a chemical reaction in the fibre allowing the absorption of the desired hue. Mordant could be uniformly applied over the entire fabric or it could be placed on a restricted area. There was little respect for old textiles in India and fragments from archaeological sites are missing. Some information with regard to weaves can be gathered from impressions of fabric left on terracotta vessels. However, there is much ethnological evidence, which can be used.

[Page – 05]

Dr. Pathak: Have we found samples of painted textiles among the cloth fragments at Fustat?

Dr. Varadarajan: There appear to be some samples of Gujarat origin painted textiles at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt as stated by Ruth Barnes in her work, Indian Block Printed Textiles in Egypt, the Newberry Collection in the Ashmolean Museum Oxford, Vol. 1, Oxford, 1997. Quseir al Qadim is synchronous with Fustat, Old Cairo, Egypt and both sites have yielded similar fragments. However, the majority of the India derived cotton fragments found at Fustat is of the printed variety. The Benaki Museum, Athens has a large collection of such textiles. The tradition of printed textiles is also to be found in Mamluke Egypt, Turkey and parts of Eastern Europe, which were under Ottoman rule. The Indian tradition was, however, the most complex.

Dr. Pathak: How were such textiles used in the domestic market?

Dr. Varadarajan: Such textiles could be used for decorative hangings in domestic and monumental structures, as wrapping and covering material (rumals) or in costume.

Dr. Pathak: Does royalty patronize it or did it serve others as well?

Dr. Varadarajan: It was patronized by both the privileged as well as by others including the temples in South India. In the absence of written records and paucity of archaeological finds we have to depend more on ethnological evidence.

Dr. Pathak: What are the differences between the old and contemporary items?

Dr. Varadarajan: The old pieces are of much finer and more precise workmanship but at the time of their production the pricing mechanism had not been worked out. The price was calculated on the basis of the price of the cloth the cost of items used in its manufacture. The cost of labour and the artistry involved were not paid for.

Dr. Pathak: What inspired your interest in this subject?

Dr. Varadarajan: I was not satisfied only with trade statistics but was also wanted to investigate the technology involved and the craftsmanship. I found that the ethnological approach was more appropriate for the kind of investigations I wished to make.

Dr. Pathak: Do you have any thoughts on the future of the crafts?

Dr. Varadarajan: I feel that mechanization will increasingly replace work by hand. Therefore this sector has to concentrate on what cannot be done by machines. I see this sector as one of great vibrancy as only the traditional workers can envision new horizons rather than designers or specialists from outside. I strongly believe that a system of education specifically by and for the craftsmen has to be established rather than one based on western models.

[Page – 06]

Tent Panel illustrate Gandaberunda

Anamika Pathak

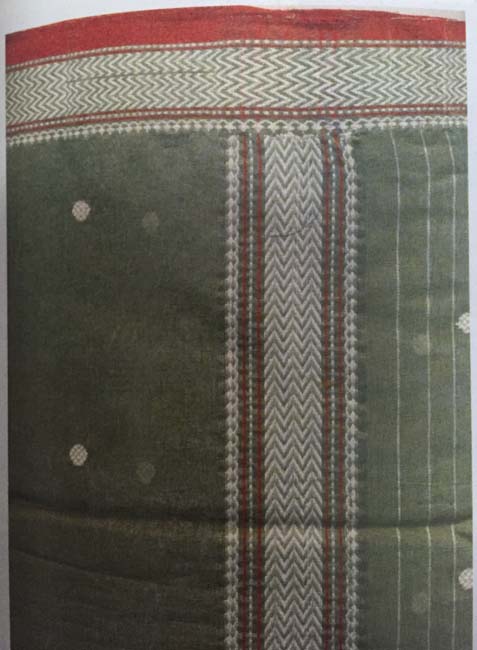

The nature loving rulers from north and south of medieval period were known for constructing gardens around monuments and have sometimes replicated even in their garments and furnishings. ‘Qanats’ or tents, among furnishing, are the most prominent examples, which illustrate the attractive gardens. Variety of fabric (cotton, silk or velvet) have been used for making of full tent along with chhatbandi, canopy, panels etc., which were decorated with gold painted, block printed, woven or embroidered techniques.

National museum has a large ‘qanat’ or ‘tent’ of single piece, which beautifully illustrate five panels of 157 x 82 cm size each, while full size of tent is 450 x 223 cm. Decorated with mythical bird, animal intermingled with flowering pattern this tent is an exquisite example of kalamkari from South India perhaps Golkonda, dates back to mid-17th century. The term kalamkari refers to hand drawn work, where outline is done with kalam (pen, which are specially created by the artists) done on cotton base fabric, which is pretreated by alum to achieve the bright and even tone of the colour. The design is drawn in a mordant solution and the cloth dye in an iron-rich black dye bath, the colour

adheres to those areas, which are treated with the mordant. This process is repeated to achieve more colours to the pattern and finally additional colours are painted directly onto the cloth to create more colours to the object. (1)

Design of ‘qanat’ show the flowering tree of different style under lobed niche while narrow vertical floral border, of contrast colour, divides the two panels and oval finale on top reminds the pole used for construction of tents. Both the portions of qanat, upper and lower, illustrate double borders; row of arches and floral creeper border on the upper border and pair of floral border is at lower end. The assemblage of three vases is on both the outermost panels. Two of the vases are filled with flowers and leaves but the central vase gives rise to a cypress tree, overlaid with attractive flowers. Birds sit, strut or fly between the leaves, creates the garden ambience. Two panels, next to these, are also filled with stylized trees and creepers that give forth a dazzling variety of flowers and fruit, crowned prominently by pineapple. (2) The lower portion of left side panel illustrates pair of lion hunting deer while two mythical creatures are on right side panel.

[Page – 07]

These mythical creatures stand around rock style arrangement are having maker-mukha (Crocodile face), looking backwards, while body is very thin, like dog’s body. Centre panel is the most striking one, show gandaberunda, (3) the double headed eagle; the mythical creature, swoops down and grips two miniature elephants, whose only traces are left. We see the underside of bird’s body with its claws clenched and wings tucked in a steep dive, stylized feathers swoop out of the body and fill the space in an outstanding pattern. Apart from these main features, the remaining portion of qanat panels are filled with flowers, birds, butterflies, fruits, leaves, geometric motifs etc. A tent with two panels done in similar composition and style is in Victoria and Albert museum London. (4) Motifs worked in maroon, white, green and blue colours have come out well on the off-white cotton base fabric, which has two joints. The loosely woven cotton lining has three joints and all joints are hand stitched. These qanats are one of the most important items of furnishing, which were often got mention in literature, (5) in bahi’s (6) and portray in miniature paintings (7). Ain-i-Akbari, the Akbar period manuscript, written by Abul Fazl devote a chapter on Farrash Khana, department specially dedicated to tents since emperors have used these tents at the time of war or hunting. This department was maintained by Farrash, whose sole occupation was the physical care of the tents. The text mentions about the types of tent, their size, double storied tent, different names of tents, persons involved in construction of tents and many interesting information. (8)

The imperial palace tents were the encampments of leading nobles, all arranged according to rank and established protocol as mentioned in Bernier’s account also. (9) Several Mughal paintings also portrays the majestic tents; whether the submission of Rana Amar Singh I (10) or Krishna Enthroned. (11)

Sometimes these tents have been shown very prominently as depict in a Mewar school mid-18th century painting.

It shows a large camp of Maharana Sangram Singh II, where he is receiving Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh of Jaipur. The tent and canopy has been done in double layer; inner layer show floral pattern under an arch on white background, while outer wall is of plain red colour. The entrance gate side has additional tent wall, which is of deep mahroon colour decorated with gold printed/painted floral pattern. Yet another painting show Akbar hunting a qamargah (enclosure), here circular tent show panels with cypress tree and flower vase arranged alternatively under an ach on the red background. (13) Although number of painted, printed or embroidered tent panels are in various collections, but it is difficult to find such artistically created royal complete tentage.

[Page – 08]

Still there are few worth mentioning complete tent, which are known for their exquisite workmanship. The famous ones are ‘Lal Dera’ of Mehrangarh in Jodhpur museum, ‘Man Singh’ of Jaipur in City Palace museum, Jaipur, Rajasthan and ‘Tipu Sultan tent’ of Mysore in Clive museum, Powis, United Kingdom. (14)

With the good line work, powerful illustration of gandabarunda, lion hunting, stylized tree filled with flowers, leaves, birds, butterflies etc makes this National Museum tent panel an excellent example, whose artists are not known.

Bibliography

- Varadrajan, L., ‘South Indian Tradition of Kalamkari, Ahmedabad, National Institute of Design, 1982; Guy, J. Woven Cargoes Indian Textiles in the East”, Thames and Hudson, Singapore, 1998,pp-22-23.

- Portuguese took pineapple to Brazil and then to India in around 1550.

- Gandaberunda; the mythical creature is more visible in Deccani iconography and found in stone or bronze sculptures and has state emblem of Karnataka also.

- Sardar. M. in Sultans of Deccan India 1500-1700 Opulence and Fantasy (ed) Haidar N.N and Sardar M., Metropolitan Museum of art, New York, USA, 2015, p-276, pl-165.

- Especially in Mughal and sometimes in European’s traveller’s account

- Day to day accounts of royal holdings.

- Beach. M.C., Mughal Tents in Orientations, vol-16. No-1, 1985, pp-32-43.

- Abu L Fazal., Ain-i-Akbari, tr. H. Blochmann, New Delhi, 1965, pp-55-57

- Bernier, Travels in the Mughal Empire AD 1656-1668, England, 1891, pp-366-67.

- Beach, op. cite, Fig-1, p-33. It is in Padshah-nama manuscript, Mughal, c.1640, The Royal Library, Windsor.

- Beach, op. cite, Fig-4, p-36. It is in Razm-nama manuscript, Mughal, c.1582-4.

- Crill. R, The Fabric of India, London 2015, pl-135, p-130

- Crill, op.cite, pl-117, p-114. It is folio from Akbarnama Manuscript in Victoria and Albert museum London.

- Rahul Jain, Textiles and Garments at the Jaipur Court, Delhi, 2016, pp: 126-129

[Page – 09]

Sustainable Approach to Rebuild Dyeing in Traditional Craft of Chamba Embroidery

Rohini Arora

Introduction

Chamba state of Himachal Pradesh was famous for embroidery known as Pahari embroidery. The most popular article made was embroidered coverlets and hangings known as Dhkanu (square coverlets) or Chhabu (circular coverlets) used for covering the ceremonial gifts as well as offerings made both for Gods and rulers (Sharma, 2009). In later centuries, unavailability of silk yarns and inappropriate use of colours adversely affected the quality of embroidered products. Hence, a sustainable approach was adopted to achieve the aesthetics of embroidery and to explore new possibilities under changed circumstances. The study was undertaken to develop standardized recipes for dyeing base cloth and untwisted yarns used for embroidery in traditional colour palette using natural dyes available locally. This would comprise of extraction, application of selected natural dyes on cotton fabric and silk yarns as well as testing of dyed material for color fastness properties. Natural sources of dyes that were easily available to the artisans in Chamba were selected for dyeing. Also, due to limitations of infrastructure available with artisans, ease and simplicity of application of dyes was of utmost importance.

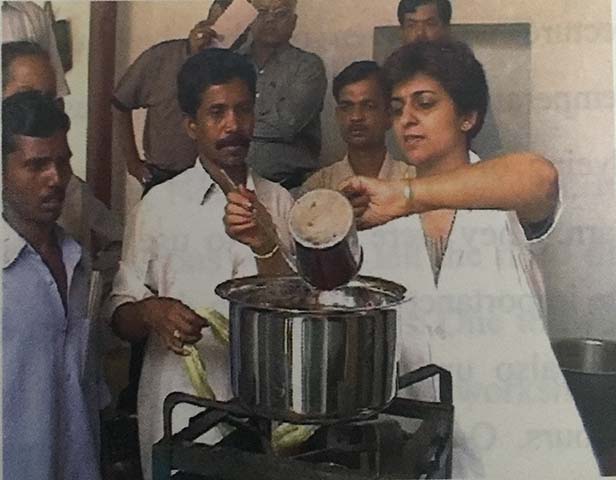

Bleached cotton fabric was dyed in a colour used traditionally for embroidery. The shades developed for embroidery yarns were in line with those used in earlier times in 18th century. Dyed fabric and embroidery yarns were colour fast to washing, dry cleaning and light. Intervention with the artisans was carried out by conducting interactive workshops and follow up field visits to Chamba. Interventions through workshops helped in capacity building of the artisans and proved invaluable. They helped the artisans to reorient themselves towards sustenance of the traditional form of craft.

Methodology

Dyeing of raw material included application of natural dyes on base cloth and embroidery yarns to develop the traditional colour palette. Dyed raw material was tested for their colour fastness with respect to washing, dry cleaning and light. Identification and selection of indigenously available natural dyes was done during the field trips made by the investigator.

Dyeing of base cloth with Harad

To prepare the fabric for dyeing, it was de-sized by soaking in lukewarm soapy water for 4-5 hrs. The dyeing liquor was made with 30% dye (Harad) on weight of the fabric (owf).

[Page – 10]

The m.l.r taken was 1:40. The grounded dye particles were dissolved in little water (approximately 50 ml) at room temperature to form a dye solution. This solution was sieved and added to required quantity of water to make up the dye bath. The pre-soaked cotton fabric was entered into the dye bath at room temperature for 45 minutes with intermittent stirring. After dyeing, the fabric was rinsed in cold water and soaped with a mild detergent.

Dyeing of embroidery yarn

Five ply untwisted mulberry silk yarns was used for experiments. The traditional color palette was developed using different pre mordanting and post mordanting procedures using selected natural dyes. The dyes used were turmeric 50% (curcuma longa), Heena 50% (Lawsonia inermis), Ratanjot 100% (Arnebia nobilis reichb.f.), Manjistha 100% (Rubia cordifolia), Tesu 100% (Butea monosperma), Pomegranate rinds 100% (Punicum granatum), red onion skin 100% (allium cepa), wood bark of 80% (Pinus sabiniana), Cone of 80% (Pinus sabiniana), Katha 50% (Acasia katechu), Calcium carbonate + turmeric 5%, 12%, 20% (1:1). The mordants used were Phitkari (Alum), Ferrous sulphate and Copper sulphate. For premordanting 10% of these foresaid mordants were used and for postmordanting 1% quantity of these mordants was used. The procedure for dyeing with Tesu has been shown below. The same procedure was followed for all the dyes.

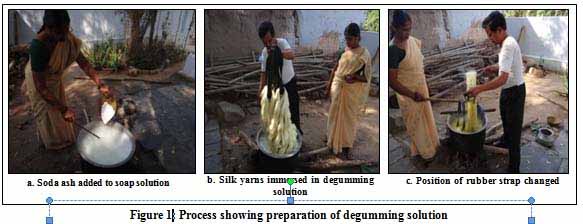

Preparation of yarn for dyeing

The silk yarns were degummed in a solution containing 3% soap and 0.5% of soda ash using 2.5 litres for 100 gms of yarn at 80°c temperature for 45 minutes (figure 1). After treating the yarns for 45 minutes, the yarns were removed from the solution and hung vertically to drain out excess of water. The yarns were subsequently washed in cold water thoroughly.

Collection and preparation of dye material

Dyes were obtained in the form of powder (turmeric, heena, and combination of calcium carbonate+ turmeric (1:1)), peel (ratanjot) as well as in solid form (katha, manjistha, pomegranate rind, pine tree bark).the solid pieces of the dye were manually broken into smaller pieces which were used for dye extraction.

Extraction of the dye

The extraction of all the natural dyes in the study was carried out in aqueous medium. The amount of natural dyes used for extraction of dyes is given earlier. The required amount of dye was added into 2.5 liters of water and boiled for 20 minutes at 100°c temperature with constant stirring. Extracted dye was sieved through a strainer.

Pre mordanting

Mordanting was carried out by dissolving the required amount of mordant in water using 2.5 litres for 100 gms of yarn. The yarns were immersed in the mordant solution for 60 minutes at room temperature. At the intervals of 10 minutes each, the yarns were lifted out of the solution, rotated and immersed in the solution again. All the layers of yarns in the hank were exposed to the mordant solution by changing direction of yarns from inside out and vice versa. The samples were squeezed and dried without washing.

[Page – 11]

Application of dye

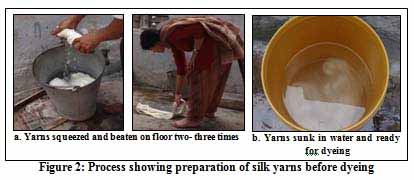

Pre mordanted yarns were thoroughly wetted in plain water, squeezed and beaten on the floor two to three times (figure 2a). The process was repeated till the yarns became heavy and sank under water in the bucket (figure 2b).

Pre mordanted yarns were thoroughly wetted in plain water, squeezed and beaten on the floor two to three times (figure 2a). The process was repeated till the yarns became heavy and sank under water in the bucket (figure 2b).

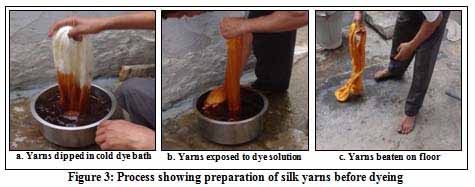

The wetted yarns were pre-soaked in the extracted dye solution prepared earlier for 10- 15 minutes at room temperature (figure 3). Direction of yarns were changed continuously and beaten on floor three to four times.

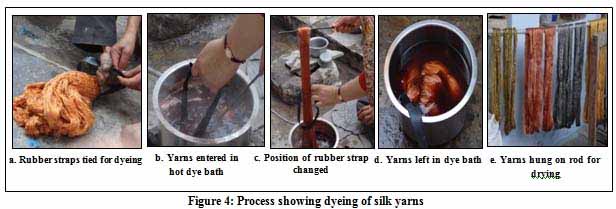

Yarns were suspended from rubber straps when immersed in hot dye solution (figure 4a). The dye solution was heated to a temperature of 80°c and pre soaked yarns were entered into the dye bath for 10- 15 minutes (figure 4b). Yarns were stirred and position of rubber strap was continuously changed (figure 4c). After dyeing, the yarns were left in the dye bath for 10 minutes (figure 4d). Finally, yarns were dried (figure 4e) and post-mordanting procedures were carried out.

[Page – 12]

Post mordanting

For post mordanting 2.5 liters of water was taken for 100gms of yarn and required amount of mordant was dissolved in water. The dyed yarns were immersed in the mordant solution for 10 minutes at room temperature. This was followed by soaping of yarns in reetha solution at room temperature for 10-15 minutes. This was followed by rinsing in cold water for two to three times and yarns were dried in shade.

Colour fastness of dyed raw material

The standard used for testing wash fastness of dyed fabric and yarns were is/iso 105- c10: 2006. The standard used for evaluating colourfastness to dry cleaning for dyed fabric and yarn is: 4802:1988. The standard used for evaluating color fastness to light for dyed fabric and yarn is: 2454: 1985.

Results and discussion

The results of colourfastness to washing, dry cleaning and light for dyed fabric and yarns are discussed as follows:

Dyed fabric

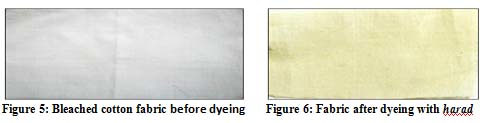

Bleached cotton fabric was dyed with harad (figure 5) to obtain the colour used traditionally for embroidery (figure 6). The rating for colourfastness of fabric with respect to washing and dry cleaning was excellent (4-5) for change in colour and negligibly stained (4-5) for staining. The rating for colourfastness to light was good (3-4)

[Page – 13]

Dyed embroidery yarns

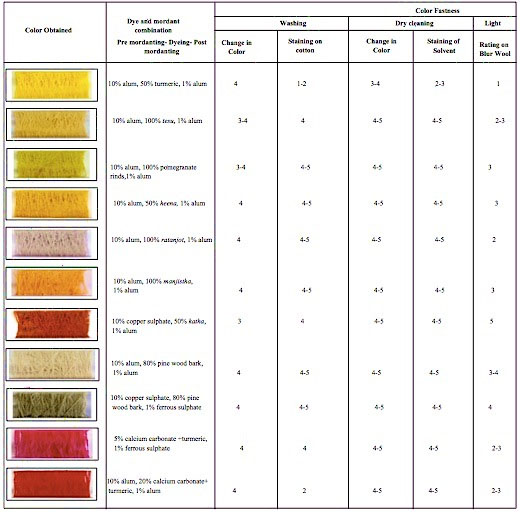

Total eleven shades were developed using 11 dyes, 2 pre mordants and 2 post mordant combinations (pre mordant- dye- post mordant) (Table attached)

Summary and conclusion

In present study, sustainable approach was undertaken to restore natural dyeing for sustenance of traditional craft of Chamba embroidery. In dyeing of base cloth, bleached fabric was dyed with harad to simulate the traditionally used unbleached fabric. The findings for colourfastness revealed that fabric dyed with harad was colour fast to washing, dry cleaning and light. Shade card in traditional colour palette was developed for embroidery yarns, which comprised of 11 shades with different pre and post mordant combinations. Most of dyed yarns were colour fast to dry cleaning as they showed excellent rating for change in colour and for staining of the solvent with the exception of turmeric which was not as good as others. Keeping the above results and the delicacy of the craft in mind dry cleaning was recommended, as most of the dyes were colour fast to dry cleaning. The colourfastness to washing was varied for different dyes and mordants. Most of the dyes showed colourfastness to washing between good to fair. The rating for staining on cotton was between negligibly stained to slightly stained for most of dyes except for turmeric and calcium carbonate +turmeric where it was considerably stained. The end use of the products was meant more for decoration purpose rather than personal use. Therefore, regular washing of articles made was not required and embroidered products should be washed separately and gently with minimum agitation. The colourfastness to light for dyes like katha, pine wood bark showed rating between good and rather good. Dyes like heena, manjistha, tesu and pomegranate rinds showed average colourfastness to light. Dyes such as turmeric, ratanjot, and calcium carbonate +turmeric showed colour fatness between average to low with few exceptions. Keeping the results of light fastness in mind most of the articles would be developed for indoor use.

[Page – 14]

Dyeing of Chanderi Silk with Natural Dyes

Simmi Bhagat

Introduction

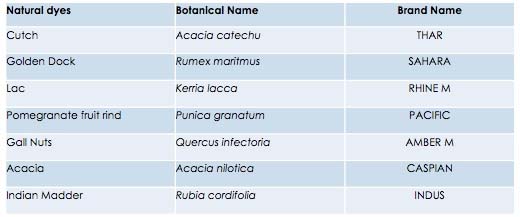

The revival of the use of Natural Dyes worldwide was primarily due to the increasing environmental consciousness. Many synthetic dyes led to various harmful byproducts during their manufacture. A number of azo dyes that released harmful carcinogenic amines have already been banned by most of the countries. Moreover the effluent discharged was also causing a lot of concern. Hence, there was an increasing realization in the textile industry as well as among the textile consumers to develop and demand eco-friendly methods of dyeing. Natural dyes offered an important alternative in this regard. Their non- toxic, biodegradable properties made them exceedingly popular. Natural dyes procured from natural wealth like plants, minerals and insects are fairly nonpolluting, more challenging, have rare colour ideas and unlimited scope to generate new shades. During last decade and a half lot of research and development work has been taken up in this area. Though the initial enthusiasm about ecological movement has subsided but natural dyes have carved a unique niche for themselves in the world of fashion and textiles and shown a slow but steady growth over the last few years. Also, globally the trend is to go back to nature and patronize natural products. In regards the value addition these

Natural Dyed fabrics or products would come under concept selling. This is a relatively new and unique concept with few players in the market and it carries a specific quality or benefit that the buyer is looking for or made to look at. This point has been proven by the fact that consumers are willing to pay more for eco-friendly products. With these views natural dyes were introduced in Chanderi too where the type of silk used is undegummed which provides the characteristic lustre and sheerness to the fabric.

Materials

Fabric: Undegummed, undyed 100% silk X silk hand woven fabric in plain weave was procured from weavers of Chanderi.

Dyes: Seven Natural dyes were used for the study. All the dyes were used as commercially available and were procured from Alps Industries Ltd., Sahibabad. The dyes used for the study are given in the following Table.

Auxiliaries: Sodium Hydroxide, Ammonium Sulphate, Non-Ionic Detergent, Aluminium Potassium Sulphate (Alum), Tartaric Acid, Ferrous Sulphate, Copper Sulphate, Stannous Chloride, Oxalic Acid, Acetic Acid, Trisodium Phosphate, Alpsfix were used for the study.

[Page – 15]

Table showing dyes used for the study

Methods

Seven natural dyes used on silk were selected for the study. Dyeing’s were carried out at three different temperatures according to the following recipes (Alps Industries Ltd) to find the optimum temperature for dyeing for undegummed silk.

Soaping of all the dyed samples was done with non-ionic detergent (0.5g/l) at 60°C for 20 minutes. After soaping samples were washed with hot water and then with cold water and air-dried.

Application of cutch

- The dye bath was prepared using 6% of dye and water (1:30); 0.25% Copper Sulphate, was added to the dye bath. It was stirred well to dissolve it properly. The material was added to the dye bath. Dyeings were carried at temperatures of 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30 minutes. This was followed by soaping.

- The dyed samples were post mordanted using 5% Ferrous Sulphate for 1 minute at room temperature. Soaping was done as mentioned above.

Application of golden dock

An alkaline dye bath (pH 9) was prepared using sodium hydroxide. Dye (10%) was added to the dye bath and stirred well. The material was added to dye bath. Dyeing were carried out at the required temperature of 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 15 minutes. Copper Sulphate 2% was added to the same dye bath and temperature maintained for 15 minutes. Then Trisodium Phosphate 5% was added to the same dye bath and temperature maintained for further 15 minutes. The dyed samples were soaped, rinsed and air-dried.

[Page – 16]

Application of lac

Samples were dyed using three different methods to achieve three different hues:

- Premordanting: The required amount of water (MLR 1:30) and alum 10% and tartaric acid 5% were added to it. The material was added and mordanting was carried out for 30 minutes at 80°C. The solution was drained and material was squeezed and dried without rinsing.

- Dyeing: The required amount of dye (6%) was added to the dye bath (MLR 1:30). Premordanted samples were added to the dye bath and dyeing was carried at different temperatures 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30 minutes. Dyed samples were soaped rinsed and dried.

- Simultaneous Mordanting: The dye bath was prepared using 10% dye, 2% Stannous chloride and 10% oxalic acid. The material was added to the dye bath. Dyeings were carried out for 30 minutes at 60°C, 70°C and 80°C. The samples were soaped as described earlier.

- Postmordanting: Un-mordanted samples were dyed with 10% shade at 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30 minutes.

- Soaping: The dyed sample were postmordanted using Copper sulphate (1%) at 80°C for 30 minuutes followed by soaping.

Application of pomegranate fruit rind

- Premordanting: (same as used for lac dye)

- Dyeing: The required amount of dye (9%) was added to the dye bath. It was stirred well to dissolve the dye. The premordanted material was added to the dye bath and dyeings were carried at 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30 min. The dyed samples were soaped, rinsed and dried.

Application of gallnuts

- Dyeing: The required amount of dye (6%) was added to the dye bath. It was stirred well to dissolve the dye. The samples were added to the dye bath and dyeings was carried on at the required temperatures 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30 minutes.

- Postmordanting: All the samples were postmordanted with 0.5% Ferrous Sulphate solution at room temperature with constant stirring for 1 minute. Soaping of the dyed and mordanted samples was done.

Application of acacia

- Dyeing: The required amount of dye (10%) and alum (5%) were added to the dye bath. The bath was stirred well to dissolve them properly. The samples were added to the dye bath and dyeing was carried on for 30 minutes at the required temperature 60°C, 70°C and 80°C.

- Soaping of the dyed samples was done s described earlier.

Application of Indian madder

- Premordanting: same as used for lac dye

- Dyeing: The required amount of dye (6%) was added to the dye bath (MLR 1:30). It was stirred well to dissolve the dye. The premordanted samples were added to the dye bath. Dyeings were conducted at 60°C, 70°C and 80°C for 30minutes. The dyed samples were soaped, rinsed and dried.

[Page – 17]

Evaluation

The dyed samples were evaluated in terms of their weight loss, fabric handle, colour strength and colourfastness, both wash and light. The results were tabulated and analyzed to arrive at the optimum temperature for Natural dyes on silk. A shade card was prepared using optimized recipe for Natural Dyes.

Findings

Since each recipe was different, the evaluation of the properties cannot be generalized or compared with one another. It was observed that dye uptake increases with the increase in temperature in all the dyes. In case of samples dyed with Acacia, Lac, Golden dock and Cutch, there is a significant increase in dye uptake values with the increase in temperature. The dyes have much less dye uptake at 60°C as compared to 70°C and 80°C.

Evaluation of weight loss was very important to determine the basic characteristics of Chanderi fabric. The degumming, if occurs, would change the entire look and the feel of the Chanderi fabric. So the weight loss of the dyed samples was determined. It was observed that there is no significant change in the values of initial and final weight of fabrics dyed with Gall Nuts, Acacia and Cutch, which indicates that no degumming took place. In case of Golden Dock the values of final weight are less than initial weight.

This can be due to the fact that the dyeing was done in alkaline conditions, which may be responsible for partial degumming. The total dyeing time in case of Indian Madder, Lac and Pomegranate fruit rind dyes was one hour while for others it was 30 minutes. These dyes indicate a marginal difference at 80°C. However the weight loss is not significant. The wash fastness of all the selected natural dyes is very good.

It can be concluded that the dyeing should be done at temperature of 70°C using standard recipes because at 60°C most of the dyes have lower dye uptake and at 80°C the handle of the fabric is getting modified in some cases. Hence 70°C can be suitably used to produce these colours. A shade card for the same was prepared using standard recipes at 70°C. It was observed that out of the selected dyes the handle is altered in case of Goldendock while Lac mordanted with stannous chloride has poor wash fastness. Hence these two were not recommended for use in Chanderi.

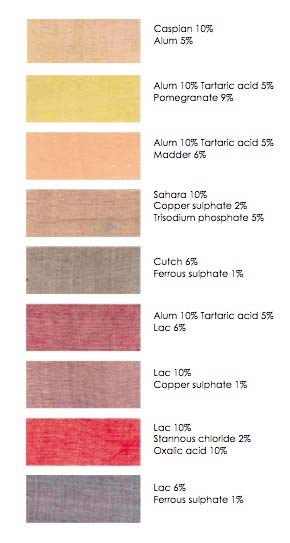

Shade card prepared using optimized recipe for Natural Dyes

Bibliography

- Gulrajani ML and Gupta Deepti 2000, Dyeing of Wool with Natural dyes, IIT, Delhi

- Gupta Sanjay 1999 ‘Value addition through Design and Trend Applications- Internet shows the way’, Convention on Natural Dyes, Department of Textile Technology, IIT, Delhi

- Jain DK 1988 ‘Fastness properties of dyes on silk’, Silk dyeing, printing and finishing, edited by ML Gulrajani, IIT, Delhi, Raj Kamal Electric Press, Delhi